MIXTAPE: Burn It All Down

September 19, 2014 - Mixtapes

rat chaos (2012)

j chastain

So here’s how I assemble these mixtapes. I play short games all the time. If I notice several games with a similar theme, I throw the titles into an Evernote page and record the number of games. As I play more games that have that theme, e.g., games in which the game world falls apart, I add them to the list. When the count reaches ten, I write up this thing.

Point is: these lists can sit around for a while before being completed. When I finished this one, I was startled to see that almost all of them were released in the same year: 2012. A good game-ruining year, if I recall. Perhaps that’s why the idea of games that fall apart from within was so potent then.

One of the main instruments of destruction unleashed that year was the rise of Twine. So maybe no game carries the spirit of 2012 quite so well as rat chaos, a game that starts out looking kinda normal but quickly crumbles into something stranger and quieter. There’s a strong branching to rat chaos that you don’t always see in popular Twine games, but it’s not used to empower the player. If you try to behave like a proper game protagonist, not much happens. If you give into the chaos a little, you die. If you go full rat chaos at the soonest opportunity, the game turns into an affecting monologue about anxiety and identity. Even the hyperlinks get overtaken by New Rat City’s emotions.

There are a few endings that seem kind of “good,” in that they say everything is fine and you don’t die. But these are written so dismissively that the game guides you toward the ending with the least apparent resolution as the “true path.” Rat chaos doesn’t just destroy the ship, it destroys the illusion that things are okay because you performed one good action.

Shade (2000)

Andrew Plotkin

Shade is much older than the other games on this list, but I played it around the same time as the others. It’s also one of the only parser-based interactive fiction games I ever really got in tune with. The beginning, which features the protagonist trapped in an overly detailed apartment doing inconsequential things, set off all my alarm bells. I felt the typical thing I do in these games: a sullen, prickly feeling that someone’s watching me, expecting me to do some unknown thing, and I don’t even want to be there. The second I start feeling that way, I start acting out, because god knows I have issues around trying to perform to arbitrary, withheld demands. Shade is, so far, the only game I’ve played of that kind where it started acting out with me. By the time the protagonist was gleefully tearing the world apart, we were on the same page completely. I mean, we died, but fuck it, we did it our way.

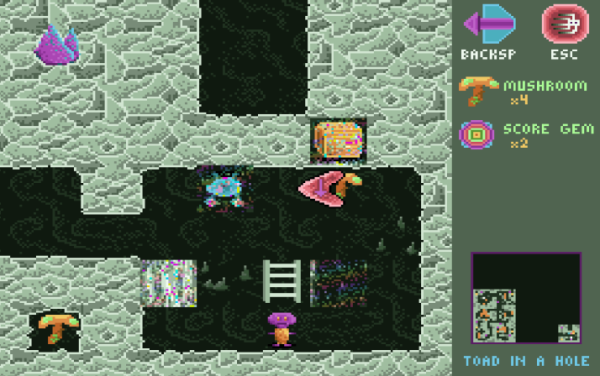

Corrypt (2012)

Michael Brough

What I loved about Corrypt is the unbelievably long con it pulled. If played to completion, or even to the point the world starts to fall apart, it’s by far the longest of the games on this list. Typically, a game that pulls itself to pieces like this is hard to pull off on a large time scale. Corrypt‘s strangeness is largely owed to how long it goes before letting its world decay, and how many rules it teaches you before it reaches that point. Not just the world, but everything you’ve learned about solving puzzles. The latter seems more gutsy to me. It gives you so much game, so much to learn, and then starts destroying that. There’s are huge risks to this: that a player might figure they’d seen what the game has to offer before reaching the turning point, and that the game can become unplayable even when someone did their best. The latter happened for me. That said, I felt satisfied at the end. I’d been thrown into something that was genuinely dangerous, and it defeated me.

Reveal (2012)

Marie Lazar, Mike Prinke, Tim Liedel, and Patrick O’Malley

Reveal is maybe the most physical-feeling digital game I’ve ever played. Every second of it is deeply satisfying to me. By the time I’d stripped the room of its walls and had grabbed the axe, I felt like I was panting – no, I definitely was – and then it kept going, it kept reacting to me in apocalyptic fashion. It just let me tear and tear until there was nothing left but me.

There isn’t much in Reveal, just a room and a few layers to tear down. But what is there is given detail and weight. The physics are modeled to give the scraps of magazines and wallpaper a sense of floppy, oddly heavy presence. There’s an appropriate back to every magazine cover, in case you drop it face down. The wallpaper textures are dense and palpably ugly. The sounds of axe against wood and different chunks of metal feel distinct. The way the pipes fall apart isn’t always intuitive. Bits and pieces are left hanging from the walls or rolling around on the floor. This is a digital game that feels like a physical object. This makes peeling it apart feel both more satisfying and a little guilt-inducing.

Anger isn’t an emotion I’ve got a great grasp on. I don’t really understand what it does to my body or how to react to it. People talk about channeling anger, but I don’t know what they mean. Reveal, though, starts by making me angry: those magazine covers, and all the explicit and implicit messages they carry, set me off instantly. But then, I feel good by the end of it. Maybe this is what people mean by channeling. I love this game.

PROMESST (2013)

Sean Barrett

PROMESST is a direct homage to Corrypt, this time with laser beams that affect slices of the world map. The game world becomes unstable this time when you gain the ability to push around the source of the beams. I found this an interesting comparison with Corrypt because I found much easier to get used to its base puzzle, with the intersecting lasers, than I did to Corrypt‘s take on block pushing and monster management. (I have a horrible time with block pushing puzzles, especially anything involving rotation like the “manta rays” in Corrypt; I think it might have to do with my difficulty distinguishing right from left.) But the second I saw it was breaking down, I split. This differs from Corrypt, where I stuck around for a while after the magic took hold. I think the change in difficulty was more disorienting in PROMESST because I’d been having an easier time before, whereas with Corrypt it was just one more damn thing. As my behavior in interactive fiction games demonstrates, I tend to shut down quickly in highly unconstrained puzzle environments.

Slime Bomb Knight (2012)

DangerDeckman

[Content warning: Rapid flashing colors]

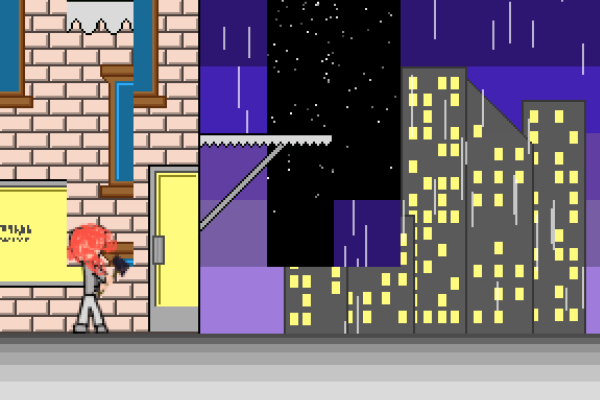

The games on this list more or less come in two flavors: those where you are the force of destruction, like Corrypt or Reveal, and those where the game is destroyed by an outside force, like Slime Bomb Knight. In this case, it’s a virus that garbles the NES-style platformer and attaches the main character’s logic to a single chunky pixel that falls from the ceiling. There’s a lot of nice glitch aesthetic in the design, but that’s my favorite bit: the heroic little pixel venturing forth from its safe ceiling to save the whole world from its inevitable doom. I feel instantly more attached to that pixel than almost any other platformer hero, because of this sense that it wasn’t meant for this job, but took it anyway. Likewise, I’m ultimately more upset that its quest fails.

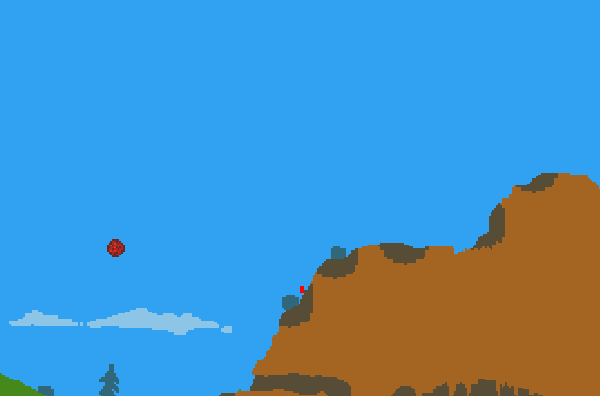

Aether Command (2012)

Danik Games

Here’s another game where the destruction comes from outside and you’re scrambling to fight it. There’s a space shooter mode at a few stations where you can hold off the attack. I’m not good at that type of game, and the world around me kept crumbling so quickly. The game can get unpredictable. Once, I had to run around frantically waiting for more of a hill to be bombed away before I could climb up and continue. The mode-switching rhythm adds to the shock of the destruction. I often found myself emerging triumphantly from a too-long shooting session only to be horrified at how little was left. If you put too much effort into the attack, it’s easy to be left in a state where the game is unfinishable.

It makes me think of how for a while a lot of big-budget action games, like the Mercenaries series, advertised their destructible environments in breathless terms. But in practice, that usually just meant adding a lot of otherwise non-functional buildings and junk everywhere for the player to blow up. Because it can’t just let you blow up stuff you need to finish the game! THINK OF THE CONTENT. But you can make the whole game about fighting that destruction, and it can feel thrilling and upsetting. But you have to accept failure as a possibility.

War Game (2012)

Pippin Barr

War Game is about the consequences of what you do in a game, and how quickly things can deteriorate if you ignore the mental toll of your actions. To drive this point home, it asks personal questions and seems to demand a certain amount of input. As time goes on, the questions and your answers alike become increasingly garbled. The elements of the war game refuse to stay in their place, and your keystrokes stop having the expected affect. There’s a crumbling game world, but there are also your own contributions being destroyed as well. It makes the destruction feel more personal, at least for me. It reached out a little more, turned into more of a metaphor about my mind being damaged rather than the world around me.

He Never Showed Up (2013)

Andi McClure

How do you make a game about something that doesn’t happen? It’s not that it’s inherently hard to do. You could make a game about waiting for someone who never comes by just having the character wait there until you quit the game. That would create one kind of effect. I think in many cases, it would leave the player expecting that they had missed something, Frog Fractions-style. That’s one metaphor for being stood up, one which focuses on the anxiety that you did something wrong that made the other person want to avoid you. He Never Showed Up takes a different approach. Letting the character destroy the world she’s been abandoned in allows the game to feel finishable, giving closure to a story about lack of closure. This shifts the player’s perspective from an observer to inside the character’s emotional point of view by making her frustration overtake the bland backdrop.

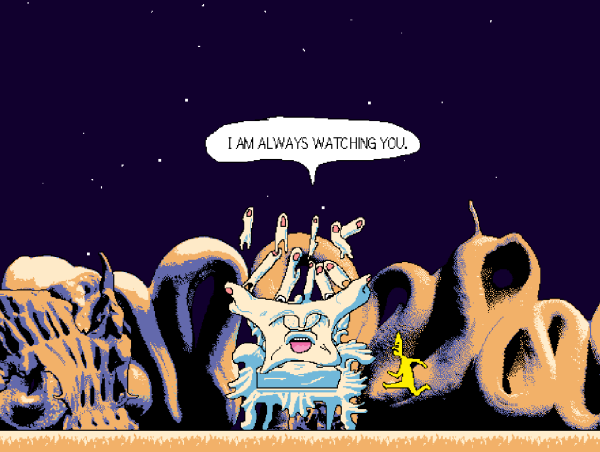

ASMOSNOS (2012)

Mason Lindroth

ASMOSNOS is a game where you destroy the world because there’s not much else to do. You get dropped on a planet and wander around until you find the button that destroys it. The art is lovely and unusual, and as you wander you see odd little scenes and creatures. Even the world map feels like a physical place; there’s a little ball you can kick around it as you walk. Nothing really stops you from destroying the world, and functionally it’s not that different from the game ending some other way. But somehow that made me feel sadder about it. The world wasn’t about me destroying it. It was just quietly doing its own thing. Those little glimpses didn’t really explain anything or tie together obviously. They suggested a big world, one I couldn’t understand in a few minutes of wandering. I didn’t feel at all gleeful ending it, like I did in Shade or Reveal or rat chaos. Those worlds begged to be destroyed; this one didn’t.

FURTHER READING

Pippin Barr on his own War Game

Channing Kennedy on Corrypt

Liz Ryerson on Corrypt

Joel Jordon on Corrypt

Cameron Kunzelman on He Never Showed Up

Chris Priestman on PROMESST

Jon Polson interviews Sean Barrett on PROMESST and Corrypt

Emily Short on rat chaos

Porpentine on rat chaos

Jenni Polodna’s character study of New Rat City

Jeremy Douglass on Shade and interactive fiction history