MIXTAPE: No Interaction

May 5, 2013 - Mixtapes

Okay, let’s talk about non-interactive games. When people in a poorly written critical essay or internet comment get anxious about a Dear Esther or a dys4ia this is an accusation they often bring out, after all. It’s fine, you know, but it’s not really interactive. What’s the implication of that? It’s not interactive, so it’s not doing anything interesting; or it’s just cheaply manipulative; or it’s somebody else’s problem, some film critic or something. Whatever the reason: this isn’t something I have to think about, because I don’t know how to interpret situations I can’t pretend to control.

Well, I ain’t a big coward like that. I’ll interpret whatever the hell I want. When something tells you it’s a game, then puts you in a situation you can’t affect, that’s meaningful. It’s different from a movie or a book, because it raises the expectation of control and then takes it away. It’s a really powerful move for a game designer to make. As the ten games in this mixtape demonstrate, this move can be deployed in a whole variety of ways.

I’ve written about this game before. The gist is, it’s a play on John Cage’s 4’33”, a musical composition made up of silence. Here, lack of interaction stands in for lack of sound. That said, this game immediately raises questions about the definition of “interaction.” After you start the game, there’s nothing you can do but wait. Still, you alter the state of the game by starting it at all. If someone else is playing, you end their game by starting your own. (Four years later, it’s probably much easier to beat.) Even in the most interaction-free game, you always make at least two changes to the program: starting and ending execution. Other games, like Execution, have made meaningful in-game actions of ending the program; 4 Minutes does the same with starting it.

In this game, you play as the mother of a roleplaying game hero. The hero wanders off as a child and faces myriad monsters, leveling up when they defeat weaker ones. You are trapped in a safe rectangle around your house. The only thing you can do is keep your child home by (awkwardly and unreliably) blocking their progress outwards. You can prolong their life that way, but at the cost of keeping them from building their stats so they can face the stronger monsters down the line. Ultimately, your kid’s longevity is pretty random. You just have to stand there and watch them thrive or die. This is a game about giving up control, because the quest being pursued isn’t yours.

Six Shots of Whiskey, Nifflas and Sara Sandberg (2011) So what makes a game feel interactive anyway? My intuition is that it’s feeling like you can change in-game variables. This intuition was more or less reinforced by a quick poll I did on Twitter ten minutes ago. In practice, of course, that definition gets slippery. In Six Shots, your actions really do control everything that happens. And yet. Maybe it’s just me, but the result is something that doesn’t feel interactive in the way we commonly use the term. The mapping between action and outcome is obscured and indirect. There are confusing dependencies between the two name choices. And when the actual story goes down you’re stuck watching passively. It’s fun, but it also struck me as something I should add to this list of games without interaction. Is the feel of interaction really just about what you can and can’t change? I think part of it is also about feeling involved in the action on a moment-to-moment basis. That feeling is hard to define and easy to fake, so I think it makes definition-writers uncomfortable.

Goddammit, Anna Anthropy (2012)Another entry exploring Anthropy’s much-loved theme of game designer as domme. In this case, you’re tied up on a couch getting horny and desperate while your mistress alternately ignores you and gets you off on her whim. The game is a series of mostly-text pages, each with an interactive header where you can wiggle the protagonist around on the couch. Sometimes there’s a pillow that you can kinda bump up against, but it doesn’t do anything. The story text describes your frustration at length. The pillow shows up as a character, too. The page structure suggests a rhythm: land on a new page, wiggle back and forth for a while, give up and read about the protagonist doing the same thing. Because you keep clicking through to new pages, there always seems to be a chance that something will be different this time, and you can flop your way off the couch or change the text somehow. But no: nothing you do matters. You’re just stuck listening to someone describe your actions with only the faintest connection to what you actually did. It’s hot stuff.

Drill Killer, thecatamites (2011)There is no escape from Drill Killer. Drill Killer will kill teenagers with drills no matter what you do. Your feeble attempts to change the course of events only produce minor, equally clichéd variations on the essentially fixed template of the slasher film. And anyway, are you really trying to pretend you came into a game called Drill Killer for a triumphant story of escape against all odds? Dead teenagers are the whole point of these things. Just relax and let go. Let Drill Killer happen.

Césure, Orihaus (2013)This is a whole genre of games that get stuck with the non-interactive label: games where the only interactions you perform are walking around and looking. Often there’s some destination, or points that trigger something happening, as in Dear Esther or The Stanley Parable. But in others, like Césure, there’s just space and some time to explore it. It features some weird architecture that’s hard to see and comprehend. Around it, a black ocean stretches out into darkness. It’s hard to tell how big the constructed space is. In a game like this there can be an implied goal to “see everything,” but Césure‘s design resists even this. Not only do structures vanish into the dark as you travel in between them, they are hard to climb and navigate even when you reach them. There’s not much to do but wander until you feel that you’re done. And in all this, I’m still fascinated with why movement seems to feel less like “interaction” than other in-game actions. Every time you move, you’re changing a game variable: your avatar’s spatial position. Why does that variable seem less meaningful than, say, the position of a crate?

Apollo 2, Robert Yang (2011) Like Césure, a game where you can’t do much but walk around. Unlike other games of this kind, there’s a tight time limit. You also have one other interaction: you’re holding a photograph that you can look at. So what do you do? The clock ticking away suggests a pressure to decide on a plan of action that isn’t present in an open-ended exploration game like Césure. I resolved to get a good view of Earth before I died. Maybe this made me miss something else worth seeing, maybe not. Adding constraints and context changes an experience, even when the basic interaction scheme remains this bare.

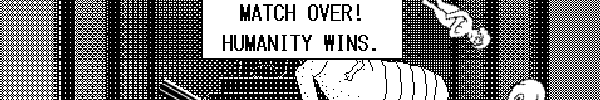

Terra Tam: The World Warrior, Leon Arnott (2012)Lack of interaction is often used as a metaphor for helplessness. Terra Tam has some fun with that trope by making you a slapstick heroine who stumbles into victory after victory through sheer luck. You wiggle around on your ass a little, and sometimes it triggers events, but the whole thing is just a joke on the fleshy uselessness of our planet’s unlikely apex predator. In a way, this plays off the exasperating and/or hilarious experience of fighting like hell to beat a boss only to have your character strike the final blow in a cutscene. All that work, just to set up someone else’s punchline? It makes an interesting contrast to Drill Killer, where your wiggling about is useless in the face of certain doom. Here, you’re helpless in the face of certain victory.

This is one of my favorite games of all time, and one I’ve never known how to write about. The first time I played it, I was in the middle of writing my PhD dissertation. This meant I was in a state of constant stress (more so than usual, even) and a lot of my leisure time was spent on the kind of short, intense games I reviewed in the early days of my blog. I didn’t have much free time, and any time I spent away from the thesis was overshadowed with guilt. I found a lot of relief in those games, because they gave me other goals to distract me from the giant, unapproachable goal hanging over my head.

This was the context in which I played Queue for the first and only time. It was, to put it lightly, not comforting in the same way. Like other games on this mixtape, Queue uses lack of interaction as a metaphor for a real-world situation where you are forced into tense inaction. But it cranks up the agony by slowing down events to a crawl. As a result, the tone isn’t playful like Goddammit or lightly satirical like Festerwood. This game feels like an ordeal. Sticking around to the end is a matter of endurance. Still, it’s not a uniform slog. The dreamlike repetition of other people earnestly telling you about their own ambitions to make game art has a pacing to it. It builds, it slows down, there’s a comic interlude, it becomes overwhelming by the end. There are a couple of moments where you’re asked to hit a button, probably just to fuck with you if you walked away for a break. (Me, I made coffee at one point.) But the overall experience is just about sitting and waiting. While I associate this game with incredible anxiety, I found the end strangely satisfying. It committed so completely to the experience that preceded it.

Grapefruit, Johnny Panic (2011)

The final game on this mixtape, “designed to be the most interactive game ever,” pushes the theme farther than the others. Is it possible to imagine a videogame less interactive than Grapefruit? Like 4 Minutes, it has an executable you can start and stop, and it displays some information. Unlike 4 Minutes, there is no recorded game state variable beyond this. (At least, none I can detect.) Fittingly, Grapefruit seems to be named after a book of “event scores” by Yoko Ono which was in part dedicated to John Cage. In both the book and the game, there is a peculiar artistic effect that arises from giving the audience perverse instructions. Do they try to obey, or at least imagine themselves obeying and then reject the idea? If they try, do they succeed or fail? How do they determine that? Where Queue uses lack of interaction to relieve the player of responsibility, Grapefruit uses it to place overwhelming responsibility on them.