Difficulty Factors as Character Traits

July 15, 2012 - Difficult Personalities / Features

Dak’kon from Planescape: Torment

If difficulty is one of the things a game can use to make characters interesting, it’s worth asking just what difficulty communicates. For one thing, difficulty isn’t just one-dimensional. There are different kinds of difficulty, and not all of them are difficult for every player. I may love both Wrex and Nami, but I’m fairly certain I love them for different reasons. The types of difficulty factors associated with a character say something about their personality. To use difficulty as a tool for character development, it would help to break out and analyze these factors.

This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive list, nor are the factors mutually exclusive. They’re more like colors in a palette. They can overlap and intersect in interesting ways. With that in mind, here are some common ways characters can be difficult, and how they get translated into personality traits.

Some damn fool scene from Harvest Moon: Animal Parade

High Maintenance

The simplest way to make a game object more difficult to obtain is to associate a higher resource or time cost with it. Particularly when there is a gifting mechanic in a game, the perceived difficulty of characters can be tweaked by having them prefer more or less expensive or rare presents. This technique is commonly used in the Harvest Moon series to distinguish characters in terms of their taste. The friendliest marriage prospects are almost always those who like flowers best; flowers are generally the easiest gifts to obtain, and the ones that represent the least value lost for an enterprising farmer. Eggs come next, and are often the favorites of other easygoing characters.

More demanding characters, as demonstrated by dialogue and behavior, are also marked by their fondness for expensive items like gemstones or hard-to-produce ones like specific recipes or rare mining finds. To court a character like Tree of Tranquility and Animal Parade‘s Luna is to take a real hit in your farm’s finances to satisfy her lust for silk and resource-intensive baked goods. To court Nami in A Wonderful Life means a significant devotion of time towards mining rather than maintaining your core business. Time is money in the Harvest Moon games, and this sort of thing adds up.

This difficulty type is a little bit distinctive to the Harvest Moon games, but not unique to them. Shale in Dragon Age: Origins is similar, preferring expensive gemstones rather than the nominally priced gifts favored by the other characters. Resource-intensive characters can also be those who take more time or effort to recruit in the first place, like Final Fantasy Vii‘s Yuffie, or those who set time-consuming quests, like Persona 4‘s Margaret.

Characters that are difficult in a resource-intensive way don’t necessarily come across as as more intelligent, like other types of difficult characters. As used in Harvest Moon, it’s an easy shorthand for indicating that a character is snobbish, spoiled, or just not immediately into you. And although this is a crude difficulty factor, and one that mostly suggests negative things about the character, it also seems to be pretty effective in making the character seem more worth pursuing. More on that in the next post.

High Standards

A related difficulty style is stat thresholding, in which a player character needs to have a certain stat level to successfully interact with a character. This is a favorite method for expressing character in stats-building dating sims like Shira Oka: Second Chances as well as in the Persona games. It is also used in a number of western RPGs where skill or stat checks determine the breadth of your dialogue options (as in Planescape: Torment) or the ability to recruit characters (as in the Fallout series).

This can serve two purposes: one, it throws up a simple difficulty barrier that keeps you from getting anywhere with the character until later in the game, and two, it can be used to express the character’s values in a playable way. It’s one thing to say Persona 3‘s Mitsuru admires intelligence, and another to literally not be able to interact with her until you reach a certain INT threshold. The first is information you absorb as a reader and the second is information you absorb as a player. When the two reinforce each other, Mitsuru’s character is more sharply defined. (When they contradict each other, there’s the possibility of either muddy characterization or interesting ambiguity, depending on how it plays out.)

Unlike difficulty driven by a higher cost of interaction, I don’t think stat thresholds make characters seem shallow. They do a similar job of making a character seem worth pursuing, but the barrier feels less arbitrary. Rather, it’s shorthand for: this person won’t care for you unless you fit a certain profile. This is not a terrible match to the behavior of real people. Another interesting effect of stat thresholding is that it gives the impression that the character in question has a higher social status than you, at least initially. In a medium where the protagonist tends to feel like the absolute center of the universe no matter what, this is no small feat.

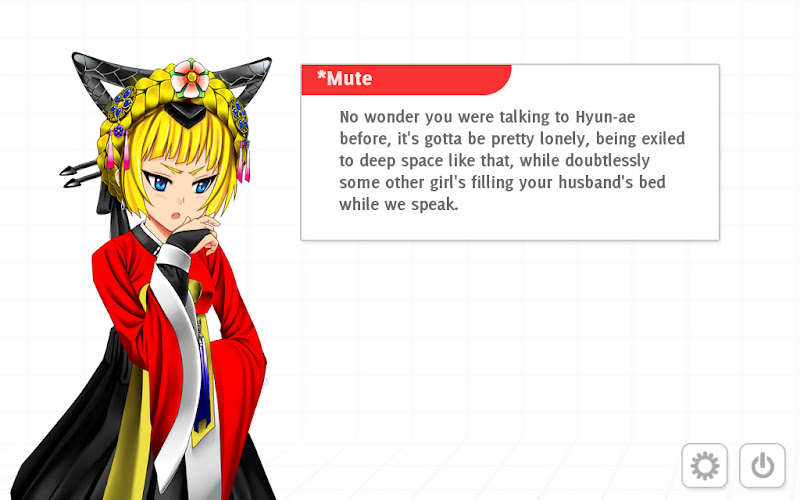

*Mute from Analogue: A Hate Story

Unyielding

A different approach to character difficulty based on resource management is when befriending a character requires sacrifices in other areas of the game. The most common version of this is when two characters are in conflict with each other, and the player must choose between them. Bioware RPGs are particularly fond of setting up conflicting character pairs of this kind, such as Mass Effect 2‘s Jack and Miranda or Dragon Age 2‘s Anders and Fenris. Analogue: A Hate Story is entirely structured around one of these conflicting pairs: the primary action of the game is determined by which of two characters you favor through dialogue options and amount of time spent with each.

The conflict doesn’t have to be with another character. The primary difficulty associated with Morrigan in the early stages of Dragon Age: Origins is that she is in conflict not only with other characters, but with your own instincts as a quest-hungry player. Dan Bruno goes into detail on these conflicts in Morrigan Disapproves, and I’ll return to this point when I talk more about Morrigan later this month.

The function of this kind of difficulty is to force choices about the parts of the game you want to explore. The difficulty doesn’t lie in the execution, but in the decision-making. In terms of characterization, this kind of difficulty is very effective at giving weight to a character’s perspective through contrast. It’s also a good narrative trick for establishing the conflicts of your story by putting faces to them and pushing the player character into an opinion. In general, it supports the impression of a sharply-defined character. I suspect a good part of Bioware’s reputation for strong characterization is due to their reliance on this technique.

Kreia from Knights of the Old Republic 2

A Hard Read

In all the above cases, the difficulty comes from roadblocks thrown up in the way of your plans. What those cases don’t cover are situations where it’s difficult to form plans at all. Characters whose reactions are hard to predict are especially thorny, especially when unpredictability is combined with any of the other difficulty factors. These also tend to be the most addictive types of characters, in my experience. Kreia from Knights of the Old Republic 2 is well-loved in part because she resists the usual Dark Side/Light Side framing of characters in the Star Wars universe. Since her reactions can’t be predicted by reference to the usual moral viewpoints, the player has to suffer more failures and pay more attention to her responses to improve their standing with her.

Likewise, most dating sims or games with dating sim elements have at least one character who doesn’t respond to things as they “should.” Kasumi and Yui in Shira Oka: Second Chances, for example, react negatively to questions about themselves and talk of emotions, which are usually surefire tactics for chatting up the other characters in the game. Hidden mechanics can also increase unpredictability. In Planescape: Torment, boosts to companion morale decay completely after eight in-game hours, leaving players scrambling to understand why all their careful dialogue choices seemed to get them nowhere.

This is the difficulty style that is most effective at producing an illusion of depth and intelligence in a character. The unpredictable parts of a system are the ones people put most effort into modeling. If a player remains interested in a character, that effort will pay off in a more nuanced view of who the character is. In theory, it seems like there should be a limit to this. At some point, more unpredictability should just make a character seem confusing and pointless. But I believe there’s an enormous space to stretch in there. If we see something that looks like a person, our brains tend to work pretty hard at giving it a coherent personality whether it’s warranted or not. This is a fine thing for a designer to exploit.

* * *

None of these factors are mutually exclusive. Memorable characters often combine several of them, as do Kreia and the companions from Planescape: Torment. Morrigan displays aspects of all four. One interesting thing about all of these factors is that they give the characters a bit of an advantage over the protagonist. Convincingly putting player characters at a disadvantage can be difficult in narrative games, and this can interfere with effective storytelling (as in Paul Sztajer’s Half Cinderella problem). Character difficulty can mitigate that problem in both a mechanical and narrative sense at once, which makes it a potentially powerful storytelling tool.